Our world is being reshaped by the idea of immediacy. Today, people expect virtual access to services, streaming content, and on-demand shopping with same or next-day purchase fulfillment. These rising consumer expectations have fundamentally transformed whole business sectors including financial services, retail shopping, travel, and entertainment. They have spurred the emergence of powerhouse digital-native brands that have pushed legacy analog companies to the margins of market relevance.

Those same forces have gathered in healthcare as well. The demand for convenience has become a full-throated cry for change. Private equity and for-profit entrepreneurs are placing sizable bets in healthcare. They see growth in the needs of an aging and chronically ill population and opportunity to disrupt the inherent inefficiencies in how care is delivered and friction in the customer experience.

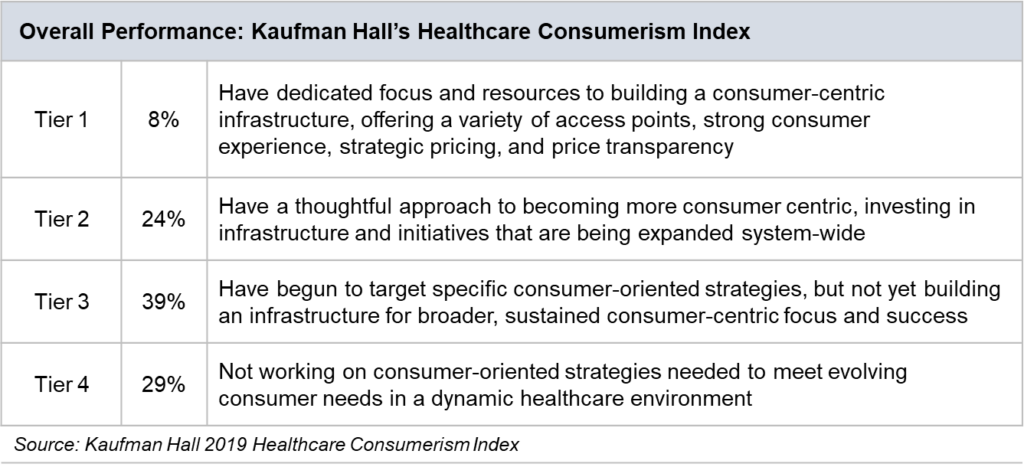

Yet, in most markets, the response from hospitals and physicians has been slow or underfunded. The 2019 Kaufman Hall Consumerism Index found that less than 10% of health systems have made plans and allocated resources to respond to digital service opportunities. Almost a third still have no active effort to create consumer-oriented strategies.

Keeping Pace with Emerging Market Threats

To keep pace with big box retail brands, payers, and technology firms moving into the direct provision of care, every health system should have a plan to move from the bottom two tiers of the Kaufman Hall Consumerism Index to the top two tiers on the scale. The key: start thinking like the new, consumer-centric market entrants and ask a different question. Instead of focusing on “how are we doing” relative to other hospitals and health systems, ask “how is the customer doing.” The insight that comes from that question will often lead in a different strategic direction—and to solutions that are more responsive to the asymmetrical, customer-centric market entrants that pose the greatest market threat.

Consider these examples:

1. A rural community hospital was wrestling with the reality of consistently having top quartile patient and provider satisfaction scores but seeing a multi-year deterioration in market performance (volumes, share, and brand loyalty). Hospital leadership felt they were “doing everything right and still heading in the wrong direction” with customers who were apparently satisfied but were still choosing to go elsewhere with their business.

In response, the CEO challenged her team to identify ways that the organization might recover recent business losses in the market. The team started its inquiry by asking “how are we doing” and focused its efforts on a predictable set of strategies, including adding amenities to the hospital and ambulatory facilities, re-engaging a consultant to enhance clinical workflow and throughput, adding outreach clinics, and tightening up referral flow from primary to specialty care.

For example, data showed that the hospital’s waiting room was a major dis-satisfier. A process consultant recommended equipping the hospital and ambulatory sites with flat screen monitors, Wi-Fi, private workstations, and a Starbucks coffee kiosk in their waiting rooms and common areas.

When the renovation was complete the waiting experience was improved. For the question “how is the hospital doing”, the answer was “better” based on patient feedback. Yet, survey data showed the underlying problem was not resolved: People were not seeking a better wait; they didn’t like waiting at all, and more amenities did not change that fact.

By starting with the question “how are we doing”, the hospital started down a path to make for a better wait. At that, they succeeded. Had they asked customers “how are you doing” the answer might have led to solutions designed to eliminate the “door to doctor” wait entirely, including virtual diagnostic and therapeutic options and advanced registration and scheduling apps. Choosing the path it did, the organization left the core service problem unresolved and created no durable competitive advantage.

2. Another hospital was working to remove barriers to behavioral health care in its seven-county rural service area. When the discussion was framed as “how are we doing,” the answer was “not very well,” with whole counties essentially having no coverage. That question prompted discussion of a range of potential solutions to recruit and distribute mental health professionals in outreach clinics one or two days a week. While the hospital made a good faith effort, the economics of the distribution model simply would not support a sustainable service offering at a level that met the needs of the underserved market.

Reframing the discussion around the question “how is the customer doing” highlighted a different set of challenges, including gaps in access and travel times, but also the ambient stigma of being seen for behavioral health issues. The combination of gaps in access and the stigma of treatment, sadly, meant that law enforcement and the hospital emergency department were functioning as the first point of contact for many people needing mental health and substance abuse interventions.

Armed with that insight, the hospital shifted its focus to digital therapeutics, including online cognitive and behavioral therapy (CBT), which closed the access gap and allowed for interventions that could be managed in the privacy of the home through online and mobile solutions. Rather than extend office hours in existing and new outreach clinics, the hospital sought to make the limitations of office hours moot by delivering therapeutic interventions essentially on-demand wherever and whenever needed for patients using video and mobile apps.

3. Getting to a medical appointment is a challenge for many people, especially those in rural communities or dependent upon public transportation. Even those with a car are often challenged by traffic, limited parking, or the challenges and cost of parking in a ramp.

One hospital system, when confronted with data showing significant patient frustration over a bad parking situation, invested in a new ramp. A competitor facing the same challenge invested in a partnership with a ride-hailing service to enable door-to-door patient transportation. The former solution was an answer driven by the question “how might the hospital do what it already does (provide spaces for people to park) better.” The latter ride-hailing solution was driven by an understanding that the customer goal was not a parking spot but getting from door-to-doctor for an appointment.

Shift Your Planning Focus

New market entrants, including technology firms, consumer retail brands, payers, and niche clinical care providers will continue to target the same customers and market space as hospitals, physicians, and health systems.

Those organizations and providers that shift their planning focus, asking “how is the customer doing” and finding solutions for consumer needs rather than “how are we doing” relative to symmetrical competitors and benchmarked satisfaction scores, will be best positioned to compete in the changing market. The fact is, an incrementally better (higher percentile rank) score on a fundamentally dissatisfying customer experience will no longer suffice when the competitive set includes consumer-centric pros like Amazon, CVS Health/Aetna, Walgreens, and a host of virtual and digital diagnostic and therapeutic solutions. The time to act is now!

Learn More! Examine strategies for competing with consumer-centric pros at the 25th Healthcare Marketing & Physician Strategies Summit, April 5-7, 2020, Las Vegas.

Plus, Forum Members can benefit from exclusive access to this session recording from the 2019 Healthcare Marketing & Physician Strategies Summit.

Michael Eaton is Senior Vice President at BVK/Brand+Lever. Mike builds valuable companies that deliver distinctive service experiences, social impact and strong shareholder returns. He helps clients see customer needs others cannot see or will not address, and execute business and operating strategies to build strong brands and generate market share growth.